You Are Not Lena Dunham

Some simple yet specific screenwriting advice!

For a while now, I’ve been playing around with the idea of a newsletter titled something like “Ten Mistakes Straight Guys Make When Writing Scripts” or “Here Are the Reasons Your Script Enraged Me” or “Why Kimmy Schmidt Stopped Being Good.” (The last isn’t technically relevant to this, I just have a lot to say about it.)

I’ve always wimped out, because I feel weird dispensing writing advice as if I am an old sage; after all, I’m still in many ways starting out in this industry. On the other hand, I’ve read and written a LOT of scripts in my life, TA’d a screenwriting class, and was nominated for a WGA award. On a third hand, I have trouble giving any type of advice online without including a paragraph about impostor syndrome.

I sometimes feel like the primary way that aspiring screenwriters get advice is not by reading books on screenwriting, but rather by retweeting nebulous advice by dubiously intelligent people. Ultimately, advice given by someone who built a career back when the entertainment industry… how do I put this… “existed” isn’t always the kind of advice you (I’m guessing 29, coastal, listens to boygenius) want. So here is a sparknotes version of my writing advice that I’m calling:

Johnny’s Quick-N-Easy Advice for the Aspiring Zillennial Screenwriter

(If this doesn’t pertain to you or interest you, forward this email to a friend! This guide is worth its weight in .celtx files, a joke they will probably get.)

1. You are not above an act structure.

There is a group of people (men) who love to sit at their computers and “bleed” as Hemingway would say. They are typically people (men) who love “film,” and write scenes consisting of two people (men) talking about “life,” and when pressed to tell you what their movie’s logline is, they will ramble on nebulously for a while, and then sort of imply that you just wouldn’t get it. (“The female character has to get sat on until she dies. It’s a metaphor.”)

You need to know act structure, and abide by it. Probably forever, but at least until you’ve written ten or so scripts. There are people who I think are above consulting an act structure, but only because they are so experienced that it’s engrained deep in their brain folds. YOU ARE NOT MIKE WHITE. Use an act structure or I will sit on you until you die.

“Use an act structure or I will sit on you until you die.”

- Johnny LaZebnik

A request regarding this subject, for close friends of mine who would like to send me a script someday: send me an outline before you send me your script. I will be so much more excited to read the following script, you will get so much more out of my notes, and you will save yourself so much time rewriting the (inevitably meandering) script that I will (inevitably) rip to pieces. Just do it. For yourself and for me.

2. Related: you are not above a logline.

Similarly, you should have a logline for your script, and your script should actually work in service of the logline. When I write for preschool shows, we typically have to come up with a logline, then extend that into a paragraph, then a beat sheet, then an outline. I really recommend doing this - it means that you will embark on your writing with a story engine rather than shoehorn one in later. A lot of people don’t know what their own scripts are about!

3. Trauma!

This gorgeous buzzword has a plethora of both denotations and connotations (I used those all correctly btw), and I’m not going to do discourse on any of that, you’re welcome. What I am going to talk about is the use of “trauma” in writing.

I would (bravely, wisely, inspired-ly) employ a Goldilocks metaphor when talking about this.

There are three bowls of writers here: the ones that write too much of their trauma, the ones that don’t write their trauma enough, and the ones that are juuuust right (like me!!!! I am perfect in every way).

Bowl 1 is for the therapy writers. These are the girlies who just broke up with their boyfriends because they are moving across the country, and their pilot is about a girl who just had to break up with their boyfriend because she’s moving across the country. You read their scripts, typically about a “normal,” “endearingly” neurotic person just trying to get through their day (she has a gay friend, if you can believe!!) – and think “Huh. I don’t think that is a tv show, but it’s certainly something that that person should be talking about with their therapist!” or, in its worst form, “Huh! I don’t think that is a tv show, and I think even your therapist might be like ‘oh my god this is exhausting.’”

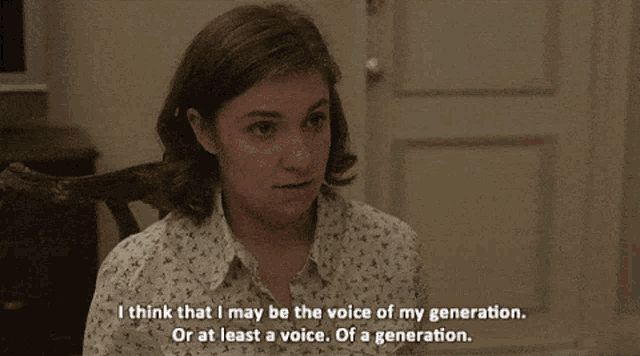

Let me state this clearly: you are not Lena Dunham. She was an anomaly – a true genius, despite many terrible pull-quotes – and her brilliance brought forth an epidemic of people thinking that their own lives were worth writing about.

You and your friends are not that interesting. I’m sorry, but it’s true. Write characters with weirder lives, who make chaotic choices. Write characters with strong wants, embroiled in taxing situations, with strong, divisive personalities. When you base characters on yourself or people you know, you often don’t want them to be problematic, to be definably “fucked up,” to be zany or funny or make bad choices. The piece of advice in this vein I’m most passionate about: do not, EVER, name characters in your script after people they’re based on. Even as placeholders. Just don’t do it.

Bowl 3 is for the people who are completely unwilling to incorporate their lives into their work. Scripts written by Bowl-3ers tend to swing big, but feel devoid of anything real. Sometimes these are absurdist comedies, where everyone acts crazy and cracks jokes. Other times, these are gritty cop shows written by 23-year-olds who grew up in Westchester and are desperate to feel “deep.”

In no uncertain terms: if you fear introspection, this is simply not the career for you. You must write from the heart. Your readers/viewers are hungry for vulnerability, and can sniff it out. You will not fool them, not even if your script is an irreverent, nihilist comedy or a kid’s cartoon (or both, like Gumball).

That brings us to Bowl 2: the sweet spot. In my opinion, when people say “write what you know,” it doesn’t mean that you should only write about things in which you have experience. It means that what you write should be grounded in real, human emotions that you do have experience with. You can write an elf archer who feels less-than if you’ve ever felt less-than. You can write about the afterlife if you’ve experienced loss. You can write about sitting on someone until they die if you’ve ever felt like sitting on someone until they died.

It’s hard to quantify in words what this actually looks like on the page (I’m not really a “writer”), but I promise you will know if you are writing from the heart. It will feel a little scary, a little cathartic, and very satisfying.

4. You must write another script.

One of the biggest hurdles I find that newer writers struggle with is that the “one script” in their head that they believe will make their career – one project that they’ve been working on for 3-5 years, and are on the 6th draft of. Let me be very clear: you must move on.

When something has been living in your brain for five years, you have a ton of preconceived notions about what you want it to be – nay, what it must be. It has to have that scene at the observatory because you’ve already directed it in your head. The character must be broken up with at the beginning of Act 2. It actually must be set in New Orleans, or the gumbo scene doesn’t pay off. Et cetera.

You probably feel incredibly aggravated, because it’s very good in your head and it’s not translating onto the page for some reason. And you don’t want to start something new, because you’ve been working on it for five years and you refuse for all that time to go to waste.

I will put this gently: all that time was wasted. You should drown yourself.

In all seriousness, your expectations for this script are preventing you from writing something coherent, and your need for it to be perfect is preventing you from completing it. You need to write something new.

Or, as Ira Glass said:

“Nobody tells this to people who are beginners, I wish someone told me. All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap. For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is why your work disappoints you. […] We all go through this. And if you are just starting out or you are still in this phase, you gotta know it’s normal and the most important thing you can do is do a lot of work. […] It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions.”

I promise that you will be startled by how easy it is to write something that is not your baby, and how, if you put time and effort and thought into it, you actually will end up caring about it and liking the new thing. Or you won’t, and you’ll abandon that too. Just move on.

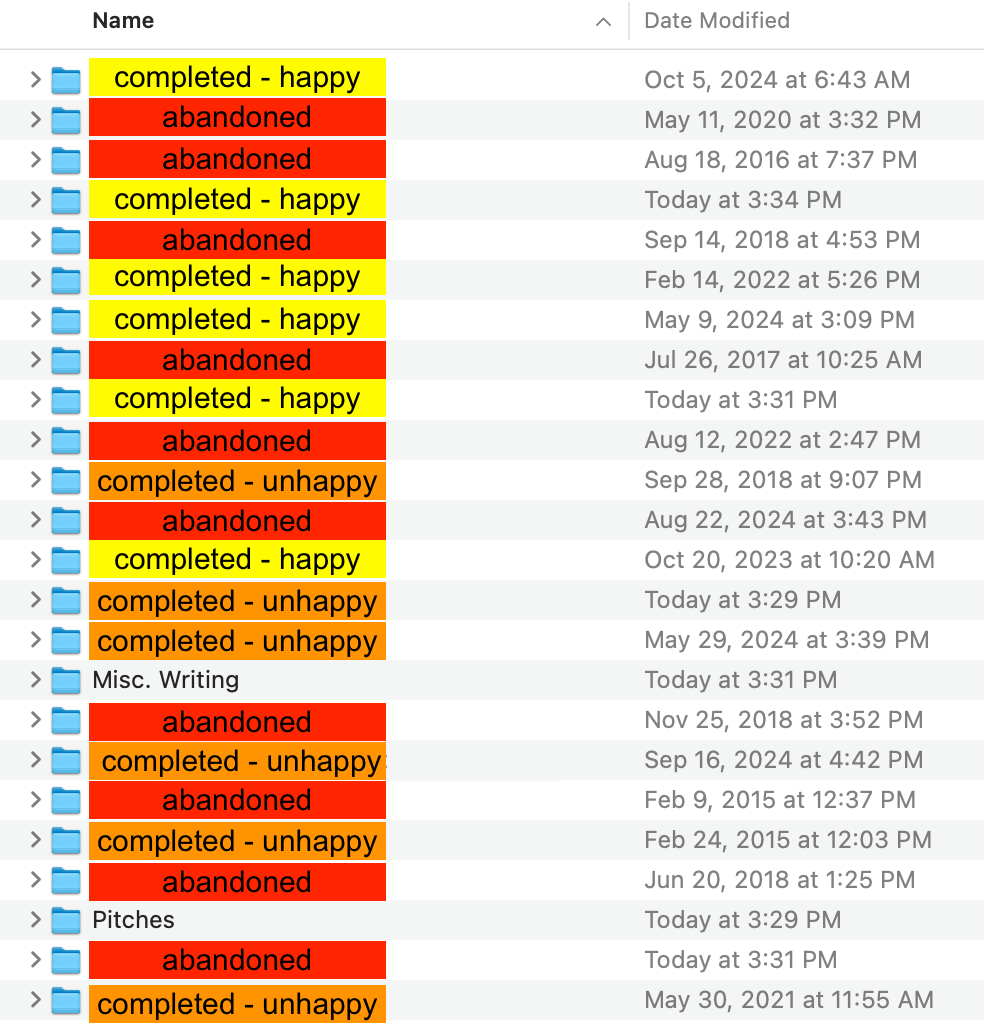

Because I feel like people rarely talk about the abandon-and-keep-writing part of the process, here’s an annotated look at my original projects folder (so this doesn’t even include my freelance work):

As for your precious baby one-ring-to-rule-them-all script: it doesn’t have to be gone forever! Put it in a box and promise yourself you will come back to it. Maybe you will!

5. Notes

At some point, you will ask people you know to give you notes on your script, and you will have strong reactions to these notes.

My notes philosophy is very firm: a good note feels like you were trying to get away with something, and someone caught you red-handed. For example, you may get a note that’s like “I don’t understand what Crystal’s motive for crashing the party is.” And you will feel a sinking feeling in your chest, and think, “Ahhh shit, she noticed that I also have no idea why Crystal would do that (and moreover, her leg wouldn’t have healed enough for her to walk by then).”

I think this note is important, because newer writers often don’t know how trust their gut yet. Sometimes you send your script to your boss, who’s sold 5 pilots and once worked very closely with Julia Louis-Dreyfus’ production executive’s sister (huge bitch by the way), and they give you a note that sets you absolutely spiraling.

Sometimes they are right, and sometimes they are dead wrong. You have to trust yourself. And if doing a rewrite per the good notes sounds insurmountable - say it with me - write a new script.

6. Have a good sample ready to go that you really stand behind.

There may come a time when someone asks you to read a sample of yours. If you are applying to jobs on the television-writing Witches’ Road, you should have a sample to send that you think is great. It is so so so important.

If you haven’t written something you love yet, you haven’t written enough. Write. Another. Script. (I would’ve made this the title of the post but “You Are Not Lena Dunham” is punchier.)

Some miscellaneous quickies:

Do not write a pilot about PAs or assistants. Don’t.

Your work can and should be “important.” But first and foremost, it must be good.

Write things that people would say. Think about how you talk to your sister and write that. Don’t write a character who says “Hey sis, how’s your new job in Philadelphia treating you?”

Don’t overlook your stage directions. They can be the difference between a good script and a great script.

Make a separate document of lines you cut out of your script. It’s sort of like putting your darlings into an assisted living facility rather than killing them.

Lastly, I know you won’t believe me, but truthfully - this post is not at all about anyone specific. These really are just the pieces of advice I find myself giving most frequently. If they resonate with you, that just means you’re not alone!

With love from Italy (it’s 1am here!!),

Johnny

you look a lot like your brother in that drawing

Thank you!!